Hi everyone,

I hope you enjoyed the first editions of this newsletter where I laid out broad themes I want to tackle in the future. You can access the archive here. I am very happy to say you’re already 400+ readers, in large part thanks to many of you sharing those first emails!

Today, an unconventional opinion: Not all payables are created equal, and finance operations can adapt to that. Take the red pill and venture with me down the rabbit hole!

The issue with payables

When I was heading content and academics at Lion, we dealt with clients of all sizes, from startups to large corporations. And I was always amazed at how swift entrepreneurs were when it came to payments, especially compared to the constant battles to get paid by deep-pocketed companies.

There was always something with the finance operations at these behemoths. When striking 5-to-6-figure deals, you would often have to talk to a procurement or purchasing department, which negotiated harshly to bring your price down (a common best practice that I believe a lot of entrepreneurs should adopt when dealing with suppliers). But the rub was in payment delays: 60 days was normal, and late payments were frequent. [By the way, I highly recommend checking out Upflow if you are having late payment issues.]

Trying to understand why, I found out that it was just business as usual: invoices get processed and paid as late as possible, especially at organizations with high working capital requirements.

And while this is a perfectly understandable approach in larger businesses, I believe it can cause underperformance for entrepreneurs and growing businesses:

It is incomprehensive: there are more items to your monthly cash out than the mere accounts payables (take taxes or credit interests for example). And all of those items can and should be balanced and analysed precisely, and possibly paid as late as possible.

It is not business-oriented: it doesn’t recognize high-value invoices and routine invoices.

That second argument is important. The Pareto principle, also known as the 80/20 rule, states that for many events, 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes.

Translating that into business and finance operations, it means that 20% of your financial resources used properly will account for 80% of the business outcomes - and that’s applicable to payables.

So here’s the thing:

Some payables and cash items you should take care of straight away, because they are so high-value to your business and create important outcomes. By optimizing your working capital requirements, you will be able to invest more, and more frequently, in those high-output items, improving your business growth.

The others you can take care of routinely, but while also analyzing them in order to understand why they were necessary to your operations in the first place. And this is where applying the Pareto principle to payables becomes strategic.

Most businesses don’t handle high-value invoices differently than routine payables— mainly because they don’t recognize what invoices are high-value or don’t have a process to treat them with priority.

I found a very interesting article by a company called Paypool sanctioning this approach to payables prioritization, and I do think it should be shared more widely. As you will see later on in this newsletter, I’m a big believer that accounting & business do not always overlap, at least in terms of approach (backward-looking vs. forward-looking), and this is a case in point. Instead of dealing with invoices as they come, it’s better to deal with them proactively.

The Matrix: High-value invoices

If you’re on board up through here, your next question must be: Ok, but how do I recognize those invoices and cash expenses that are high-value?

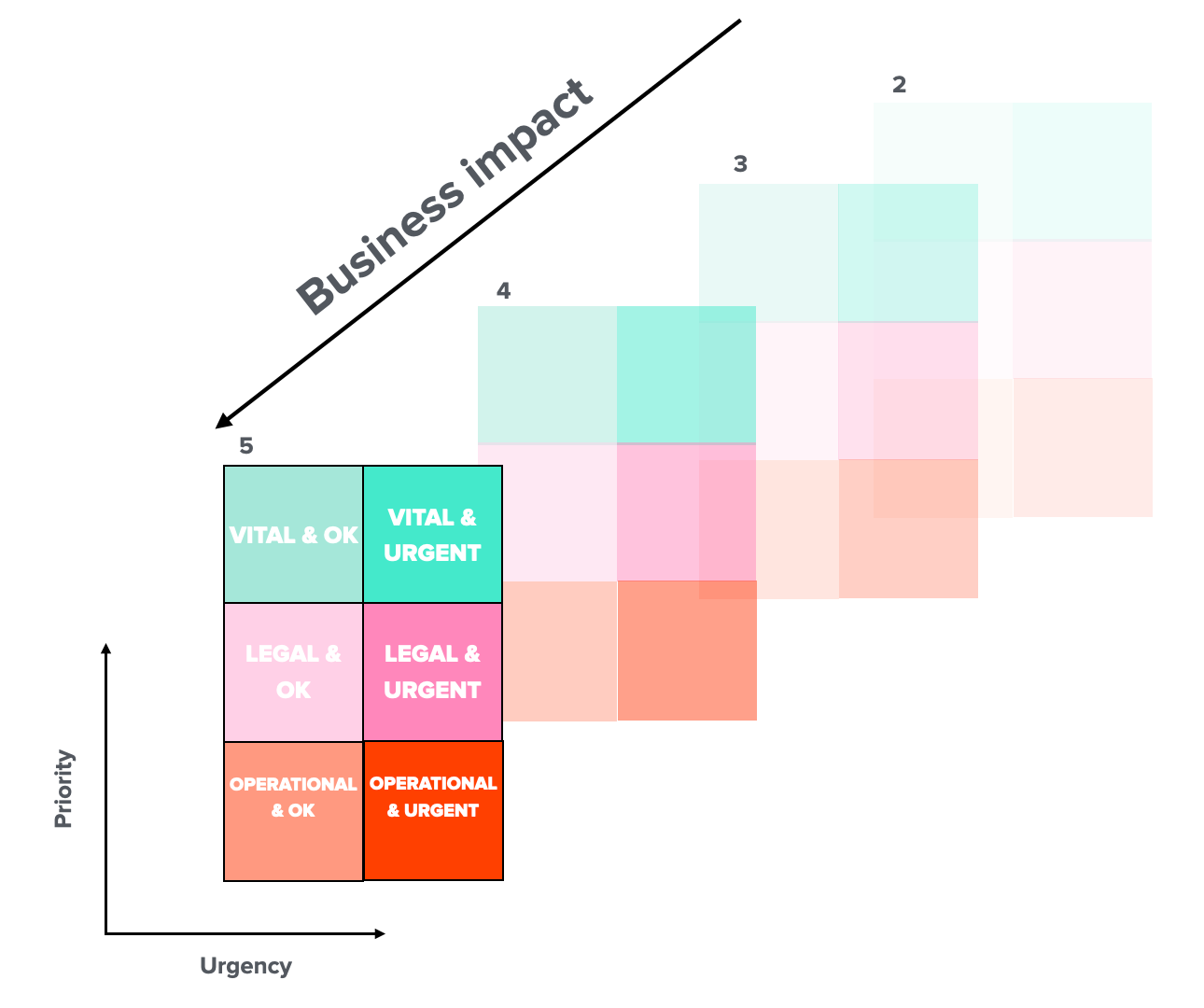

I want to share the framework I’ve started building to deal with payables. It has three axes:

Business impact: each item has a score of 1-5 determining its impact on core business. Incorporation fees for a new subsidiary or Slack fees, that’s a 5; custom company-themed socks or bikram yoga sessions, that’s a 1. Now, if your business priority is employee satisfaction, then one could argue for rating things the other way around. You just have to arrange business impact based on your overall strategic objectives, which I assume for most is revenue growth.

Priority: the categories we use are vital, legal and operational. Vital is mostly team and HR expenses, legal are the things you’re obligated to pay (e.g taxes), operational is everything else.

Urgency: this one is simple. Everything has an urgency of “OK”, until it isn’t anymore, and then it becomes “Urgent”. Here’s the very unorthodox bit: this does not depend on overdue status, but on your relationship with the supplier (leaving leeway for negotiation, agreements, etc.).

So the matrix would look something like this.

The absolute top priority things are therefore in the top right corner of the first table, and all of the rest can be arbitrated by your team and gives you a path to analysis and process optimization.

If you’re not a fan of 3D-matrixes, which the math nerd in me can still understand, you can simplify things by blending the priority ladder with business impact. Thus 2 axes: impact vs. urgency.

The important thing here is to construct a framework that works for you and your business. Perhaps you have a big stream of projects, and so everything project-related is high-value while the rest is less important. Or perhaps you rely on external consultants and contractors, and you need to prioritize their payments to maintain good relationships and improve output. It all depends on your business; the matrix above is just one example of how you could do it.

And if you’re wondering how all of that works in operational terms, the matrix I have is embedded in the AirTable dashboard that I presented last week. I just drag and drop invoices as I see fit, which is very convenient.

One last thing that’s important is to collect information about supplier relationships on the ground. This is why we have a principle of Ownership, which I’ll talk about in one of the next editions.

Let me know your thoughts about the process, or things you have implemented that work for you when it comes to payables prioritization and handling invoices!

In the papers 🗞

As this is only the third edition of this newsletter, I want to try new things regularly. This week, I’m adding a section of finance-related readings I enjoyed recently. Tell me if you think this is valuable :)

A great commentary by value investor Safal Niveshak on the rise of EBITDAC (Earnings Before Interests, Taxes, Depreciation, Amortization and … Coronavirus). Yes, you read that correctly. After WeWork’s Community-Adjusted EBITDA (how’d that work out again?), this is yet another take on earnings arrangement and numbers tweaking. Accounting decisions and business reality are separate things.

An interesting review of Netflix’s accounting principles, and particularly how the company accounts for its content assets. Again, accounting decisions and the business do not always overlap.

Closing out this Accounting vs. Business theme, here’s a side comment by Byrne Hobart in his masterful The Diff newsletter: look for the section A16Z on Accounting versus Economics (and subscribe, because it’s very insightful).

A long form profile of Social Capital’s controversial founder Chamath Palihapitiya. Worth the read!

Payment in Kind 🎁

If you enjoyed, share this newsletter and make sure to subscribe if you haven’t👇

And for this week’s pop culture reference, I’m showing up very late to a party. I’ve just started watching Showtime’s Billions and I must say it’s a bingeworthy show for finance lovers, pitting hedge fund managers vs. US Attorneys. I’m sure there’s a ton of great investment wisdom in there, too.

As the main character Bobby Axelrod notes in one of the very first episodes, “Here’s what they didn’t teach you at Stanford about investing: every time you can, put a company in your mouth.” I think that’s great advice!

Until next week! ✌️