Inartifical Intelligence

A humanist take on the new Golden Age of AI

Hi there, this is Younes!

Long time, huh? I recently left my position as CFO & Director at the investment firm The Family, where the last year and a half has been absurdly busy - too busy alas to post regularly.

While figuring out my next full-time gig, I figured I might as well get back to writing. I have no idea what the format will look like compared to previous Chasing Paper editions, but there are tons of things I haven’t had the opportunity to talk about, so here it goes.

As a refresher, Chasing Paper is a newsletter giving my perspectives on finance, strategy, tech & innovation - and how they interact.

If you haven’t, subscribe now:

Enjoy!

Seven years ago (sic), I wrote what I then considered a thought exercise: The future Da Vinci is a robot, on how AI could gradually invade the most human activity of all: Art.

Little did I imagine that in just a few years time, I’d get to play with generative text-to-image AI applications (DALL-E, Stable Diffusion, Craiyon, Wonder and the likes) with my 3-year-old niece prompting stuff like “pirates wearing dresses and eating marshmallows” or “rabbits playing a football game” (both illustrating this article).

Incidentally, ChatGPT seems to be all the rage nowadays, with people using it for a wide range of unexpected applications, especially by implementing it in their work routine, such as writing, reviewing or commenting code, or adding it to their daily workflow.

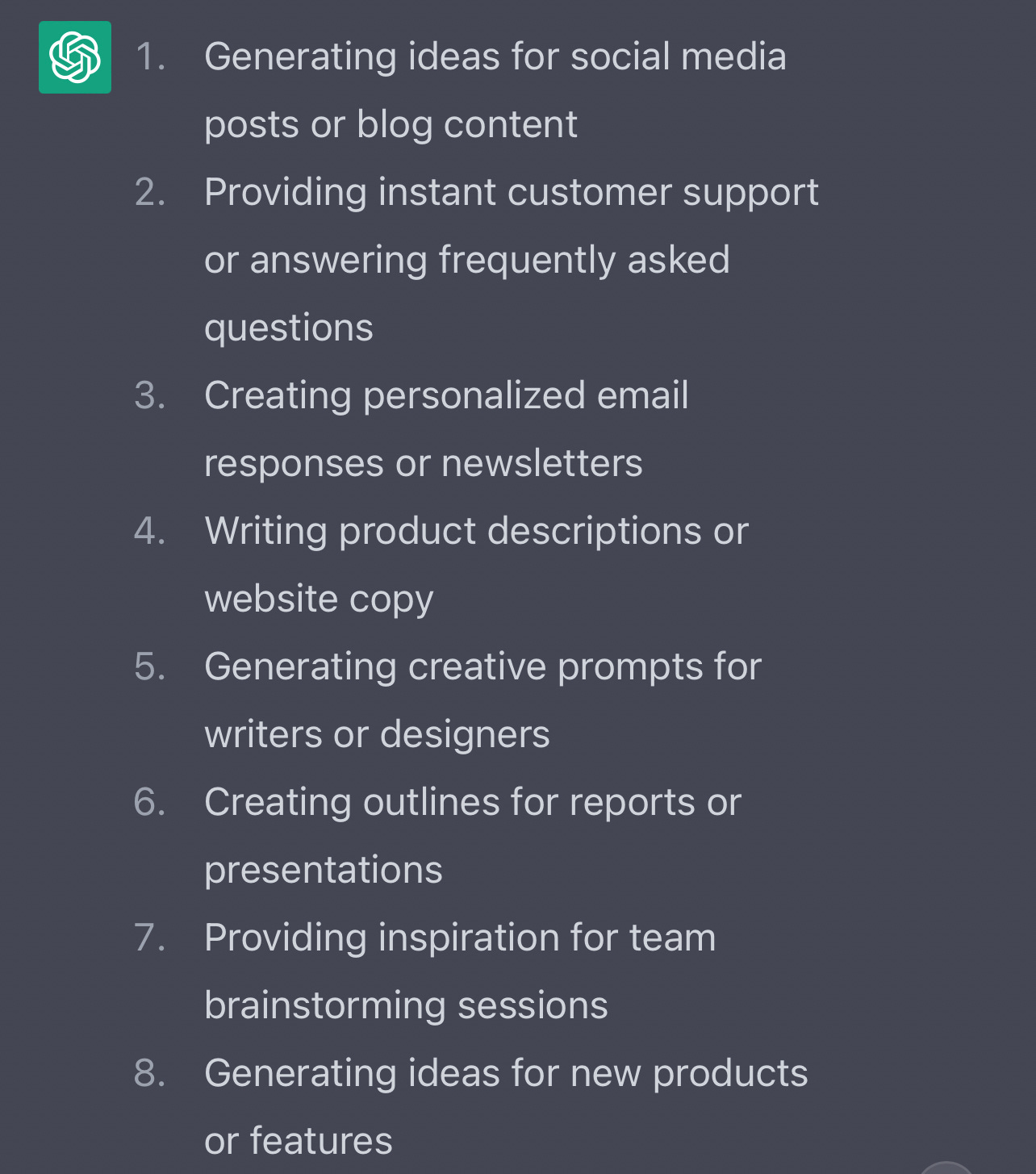

Since ChatGPT is trained with human feedback (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback), and millions of humans already conversed with it, I thought it would be fun to ask ChatGPT itself some ways it has been used in daily work for other users.

Here is its mesmerizing reply:

As revealed, plenty of the daily tasks of millions of qualified workers can already be outsourced to a free (for now) AI chatbot. Those advances are astounding, and yet we’re barely scratching the surface of what AI will be able to do.

Copywriting, CRM, marketing, content creation, product or software development, financial analysis, even consulting or teaching could all be radically transformed by implementing trained algorithms into our daily workflows.

While we’re still far from ubiquitous AI in our worklife, for a large number of reasons (high server usage and energy consumption, accessibility barriers, lack of close-ended applications, questionable UI, etc.), the pace at which we’re advancing is remarkable, as revealed by the anecdote opening this article.

A lot of entrepreneurs are now building applications on top of OpenAI or other AI and machine learning platforms (Layer 1s), which is both very exciting and thought-provoking.

With a new Golden Age of AI advancing, we’re likely to see a swarm of hyped-up, VC-funded companies that will end up being wrong bets (think ChatGPT-based customer chatbots, illness diagnosis engines, homework support tutors, etc.).

But that’s not the main issue: more importantly, we should question the irruption of AI into our lives.

Specifically, we should consider what biases AI brings along when replying to our prompts. Some users have already revealed what blatant biases, discriminations or errors are inherently present within the algorithm, that is without even factoring in the malicious attempts at tricking ChatGPT to learn more biases or false truths (which by the way, even if for information purposes and to evidence biases, only makes it worse).

As impressive as the new AI applications are, it should be remembered that learning algorithms are only as good as the data they’re fed with. Notably because for now, AI assistants will not look for the truth or correct answer when prompted with a query ; rather they will seek to provide the answer that sticks the most to what its database (say, the Web) or the people correcting its learning algorithm have said previously.

Put simply, the algorithm knows that on average, the answer it gives is the expected answer to the query - or it infers it from output data.

Apart from the ethic considerations - which are tremendously important but not my point here - trusting the algorithm too much could have important adverse business implications and risks, such as:

Decreased differentiation among competitors: imagine having the same exact marketing elements, publications, product developments, ideas than competitors. AI could very easily lead one to blend in rather than stand out. Same goes for every application of generative AI: cover letters, blog post content, song lyrics, whatever usually comes from human inspiration.

Misinterpreting off-pattern signals: if used in an analytical capacity, AI could lead to misinterpreting signals it has never seen before. Especially, those signals could very well be indicating a crisis or conversely product-market fit. How will managers act when incorrectly advised by their algorithm? Will they transfer some of the risk to the algorithm (much like they already do consulting firms) or will they recognize the algorithm might misinterpret something?

Reduced radical innovation: by suggesting things it has seen somewhere else, AI does indeed help with creator’s block, but it also suppresses any form of newness and radical innovation. How long before relying on it becomes a liability rather than an asset and locks incumbents into a stream of failing strategies (because already washed out)?

Of course, not all businesses and activities need to be unique and unpredictable. Some are purely execution-driven. And while we’re in the infancy of work-related generative AI, many will make fortunes arbitraging opportunities and catching low-hanging fruits.

My take however is that the tools to radically improve execution output thanks to AI will come and generalize, sooner than we expect.

When this comes, humans will be required more than ever : we have an incredible capacity at breaking patterns, creating new things, innovating - which will all be the key to business success, and to not falling into AI-induced biases that could set us back rather than push us forward.

In the meantime, if you have cool AI apps, I’m all for it!

Cheers,

Younes