Hi everyone,

It’s Younes from The Family. This week on Chasing Paper, a deep dive into a whopping $120bn industry: gaming. You’ll notice that today’s email is quite a bit longer than usual (which is why there was no issue last week), but I’ve been wanting to do some industry-specific focuses for a while. Let me know if you like it :)

As a lifelong gamer, the recent unveiling of Sony’s Playstation 5 was an eagerly awaited event that got me looking at the overall industry. I’ve also recently been randomly introduced to several entrepreneurs launching indie games / indie game studios, so I read a bunch of things around gaming. So here are my not-so-processed thoughts about the space - always with a financial angle ;)

Hollywood & Silicon Valley

Gaming is an industry in which financial returns are concentrated in a few hits.

Incidentally, California is home to two very interesting industries that both share this trait: film and tech. I believe a lot of dynamics from gaming can be derived from a comparison with the other two.

1/ The new Big Entertainment Monster you saw coming from miles away

It is now cliché to state that video gaming is a mass medium. 40 years in the making, the industry has managed to expand from hardcore gamers and nerds to all demographics, and has produced countless hits for generations of avid gamers.

What I find fascinating is that it’s an industry that keeps biting pieces off other industries’ turf, and notably Hollywood.

Many actors have portrayed characters in video games (Gary Oldman, Ellen Page, Kristen Bell, Keanu Reeves). And while most of those parts are all about the paycheck, I can imagine a future where actors turn down parts in movies to work on a game, lured by the exposure and higher pay.

And importantly, the gaming industry is a bigger threat to any given movie studio than any direct competitors. As Netflix elegantly said in its 2018 earnings report: “We compete with (and lose to) Fortnite more than HBO”. In a market desperate for people’s attention, few companies can absorb as much of a user’s screen time as do gaming companies.

This is so true that several artists have started using games as a distribution channel for their art, bypassing traditional media and raking in tremendous attention.

If you haven’t, you should watch Travis Scott’s live performance on Fortnite in April 2020 during peak lockdown. Less than a month later, Christopher Nolan decided to release the trailer for his latest movie exclusively on Fortnite.

Why? Because Epic Games’ Fortnite is a blockbuster with 78.3m monthly active users spending a mind-boggling 3.3bn hours in-game every month. And there are many other games reaching similar numbers that could now serve as a distribution channel for new music, films, etc.

Currently, the ways to do this are simple and limited: (a) you have Travis Scott or Christopher Nolan’s leverage and can negotiate deals directly with game studios, (b) you wait until Rockstar, EA Games or whatever studio wants your music in-game, or (c) you place ads. I believe there’s a big opportunity in finding new marketing channels through games and gaming, but more on that later.

So gaming, like movies, is a bid for people's attention during their leisure time. As such, movies and gaming are direct competitors: while "movies" and "gaming" are separate industries, they also aren't, because again they're competing for the same dollar and the same screen time.

2/ Tech and Gaming: a friend is a foe in disguise

If gaming is cannibalizing Hollywood, then tech is trying hard to cannibalize gaming.

Let’s start by noting that tech introduces large scale gamification in all aspects of our lives.

This is clearly the case for emerging consumer applications. Sports? Strava, Fitbit, Peloton and Freeletics are examples of a gamified athletic experience. Education? Duolingo. Organization? Todoist. Personal Finance? Revolut or Robinhood. You get the idea: the tech industry applies game-design elements and dynamics to non-game contexts (in layman’s terms: real life).

This is also true for business applications, especially in HR - gamification is used to increase employee engagement, facilitate onboarding, etc.

From a financial perspective, that is a good thing for those applications and products because gamification creates stickiness, which in turns generates more revenues.

More importantly, Big Tech companies, and especially Facebook, have also been facilitators for gaming studios: Zynga and other gaming companies have thrived thanks to Facebook’s incredibly large user base.

But it’s even more interesting to look at the two-way relationship between a giant of hyper-casual gaming like Voodoo Games and Big Tech companies like Facebook or Google. Voodoo needs the distribution power of Instagram or Play Stores to acquire new users [🇫🇷], but it also thrives on ad placement and monetisation that only a few advertising players are capable of providing.

We already established that gaming companies are dangerous to its fellow competitors for your attention. As a matter of fact, gaming companies are friends and foes to Big Tech companies. This is especially true as the latter are failing to rein in the upstarts of the gaming industry: both Facebook Gaming and Google Stadia are disappointing users, and seem like they’ll end up as loss-making bets.

3/ Power law, blockbusters and venture returns

The comparison with Silicon Valley and Hollywood holds true when it comes to financial returns.

Venture Capital is a business of home runs: only a few investments will represent a disproportionate share of total returns. VCs make a lot of attempts to find 1 or 2 good companies per vintage that will return the fund. And it doesn’t matter what happens to the other investments as long as those wins are large enough.

Similarly, the hyper-casual gaming industry (think mobile games you play in the subway) has skewed returns, because unlike mid-market and hardcore games that earn money through user loyalty and in-app purchases, they rely on advertisements and high download volume. Obviously, out of 100 games, maybe 1-2 (with luck) will hit the threshold and make returns high enough to cover the time and money invested in all others. Therefore, the rational thing is to treat each game like a potential loss and realize quickly which games are going to be hits to double down investment on ads, etc. Typical Silicon Valley dynamics.

Unsurprisingly, Hollywood is a blockbuster industry as well. Movie studios often reach 8-digit budgets to develop, produce, market and advertise new releases. Sure, there are indie features made on small budgets that sometimes break through, but more often than not high grossing movies have high budgets. The opposite is not true, however, and the economics are fickle: lots of movies have gobbled up financial resources only to disappoint at the box office. This is why Hollywood's always been quick to double down on franchises that audiences already like. With franchises, studios can count on merchandising, international distribution, and VOD/streaming rights to come along with ticket sales, increasing revenue and favoring those that are already thriving.

The same goes for games produced by major studios. A lot of resources are invested in the making of a videogame designed for hardcore gamers. Once a studio has found a recipe that works, you can be sure that the franchise will keep growing and the cow will continue to be milked. And in many cases the sequels are actually well orchestrated and generally better than the originals (Uncharted, God of War, Red Dead Redemption), unless they are part of the cohort of games with annual editions (FIFA, NBA2k, Call of Duty, and the like) in which case you may well not see any difference over the course of several years.

These games make money on the initial sales, of course, but also by enticing players to buy additional packs (add-ons) to expand the storyline and gaming experience, to buy resources in-game to become a better player, to subscribe to online features, to buy merchandise, with licensing deals, and through spin-offs and sequels. Typical Hollywood ( sequels, spin-offs, merchandising, extended cuts, director's cuts, etc.).

4/ In terms of HR, gaming brings the worst of Silicon Valley together with the worst of Hollywood

In today’s business world, it’s rare to see someone bragging about their teams putting in 100 hour work weeks. Yet, Dan Houser of Rockstar Games has. The gaming industry has what game developers call crunch culture: intense periods of work spanning over months in order to meet release deadlines, similar to the rhythm that tech companies can impose on their workers with growth expectations.

But at least tech workers trade off the intensity for high salaries and equity. Yet in a way that’s kinda similar to Hollywood paying mediocre-to-low salaries to workers entering the space because they love it, game developers earn significantly less than other types of developers.

Bottom line: it’s a tough industry to work in.

Platforms

Gaming is an industry that serves as a perfect illustration of the platform economy.

5/ From Hardware-as-a-Differentiator to Hardware-as-a-Service

Ever since I was a kid, video game console releases have been a big deal. I know I’d buy magazines, surf the web (sic) and engage in forum discussions to decide what platform to buy. A home video game console came with a whole ecosystem of exclusive games, accessories and features that make choosing the right one a big deal. If you can’t play a game with your friends because they have a different platform, the decision becomes critical.

But gradually, the importance of hardware has decreased. Each manufacturer still comes up with its exclusive games and features (esp. Nintendo), but most of today’s blockbuster games can’t afford to not be on all platforms. Some of them have even started to allow players to play cross-platform online games.

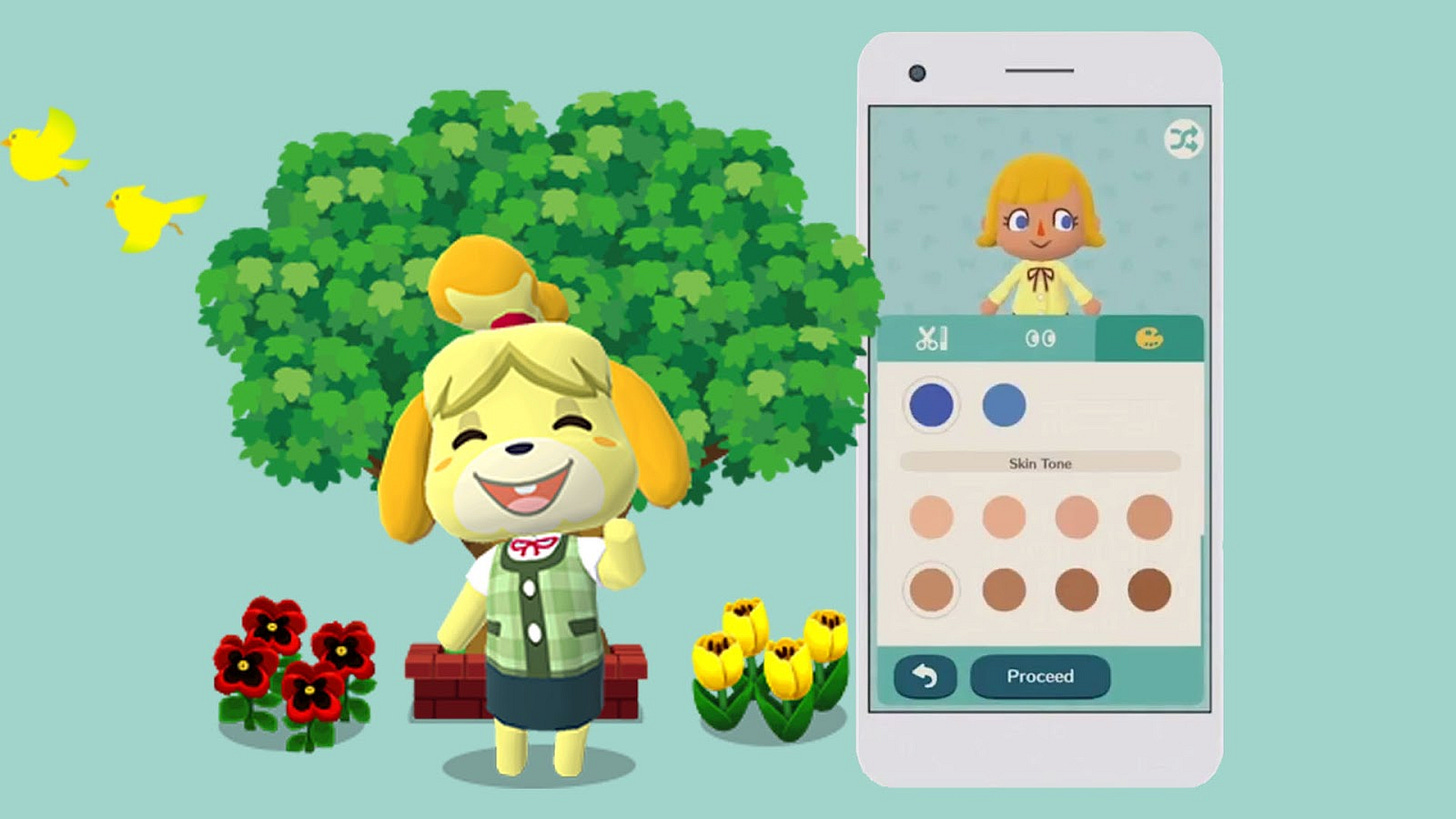

Mobile has also changed a lot of things in gaming behaviours - for instance, the Switch is a direct result of that impact for Nintendo, trying to preempt the switch to nomadic gaming. However, Nintendo still made its most famous franchises available on mobile last year (Mario Kart Tour or Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp). You just can’t skip mobile.

Going forward though, I think streaming will increasingly push the importance of hardware to the side.

Whether you’re Sony or Nintendo, selling subscriptions to your exclusive game licenses and ecosystem, available on any platform, can help increase revenues, as well as decrease your business’s capital needs. And it might bring gaming to even more users (although that is not necessarily true, as you can read in this mind-blowing piece about cloud gaming).

If that paradigm emerges, the interesting thing is that Big Tech companies have no ties with game studios in terms of exclusive deals, but they do have computing power and servers. Perhaps Microsoft has the upper hand in that respect.The question is: will hardware manufacturers remain relevant and can the gaming experience be completely revamped?

6/ Games as platforms

It’s not only the hardware, it’s games themselves that can be considered as platforms, with the seemingly infinite possibilities some can offer.

Minecraft’s success is somewhat dependent on that versatility. The game can be anything you want it to be, and so it just makes sense to spend time exploring different worlds, watching other people’s creations, investing time (and money) into yours, etc. The more people play, the more incremental revenue the game makers earn. (NB: Mojang Studio, which develops Minecraft, was acquired by Microsoft for $2.5bn)

Grand Theft Auto V is also a prime example. GTA has always been very permissive for gamers. And I’m not talking about the storyline or gameplay. I remember “hacking” into the files of my Vice City edition on PC to add crazy mods to certain vehicles. Well, picture that times 1,000 to understand the possibilities offered by 49 square miles (sic) of completely customizable maps and objects.

Not only did GTA V earn a whopping $1bn in 3 days when it came out, it is also the most profitable entertainment product ever created with more than $6bn generated through micro-transactions for add-ons, subscriptions, updates, online contests, etc.

A single blockbuster can have a good yield, but turning a blockbuster into a platform is a guaranteed cash machine.

7/ The rise of gaming services

Along with consoles and games, there are also platforms servicing gamers.

With 2bn gamers in the word, the range, depth and quality of content and services needed to create better gaming experiences keep increasing. And several platforms rely on user-generated content to provide those gaming experiences: the likes of Twitch and Discord are constantly growing apps built to cater to gaming fans’ needs.

What’s interesting is that these platforms can enable standalone businesses to rise from the ground: a single Twitch streamer can easily make $5k/month while some of the bots built for Discord rake in tens of thousands every month.

All of this represents a growing ecosystem with multiple opportunities for entrepreneurs: tournaments, competitions, gambling, analytics, streaming, etc. are all eagerly waiting for new business models to take them to the next level.

Distribution: Super Smash Bros Brawl

With a market that big, grabbing players’ attention - whatever your business model is - is an ongoing battle.

8/ Hyper-casual publishers have distribution power over independent game creators

In the world of hyper-casual gaming, returns come not from avid players (“whales”) investing to get better and better, nor from any other kind of in-app purchases. Rather, it’s the number of views that determine the ad revenue, and thus the number of downloads is what matters. It is a number’s game that gave birth to giant companies such as Voodoo (into which Goldman Sachs Investment Partners poured $200m in 2018) or Ketchapp (acquired by Ubisoft in 2016).

These companies are powerhouses when it comes to mobile gaming: Voodoo ranks #1 on the App Store nearly every month in total number of downloads. And they have built an incredible machine in terms of economics: they have in-house developers working on dozens of games at the same time (remember, skewed returns), have precise KPIs in terms of marketing spend needed to launch a game, are able to predict which ones are going to be successful early on, and have the financial power to double down intensively on winners. The more money they make with one hit, the more they are able to release new games, optimize distribution and scale, and invest in future winners.

But these companies also have an incredible way to monetize their distribution power: they publish games for independent game developers. The deal sounds sweet to any passionate game designer working from their bedroom: focus on building games, and if one of them shows a sign of being a possible winner, we’ll take care of the distribution so you can focus on what you like, which is making more games. However, it is a deal with devilish terms.

Usually, publishers pay a substantial amount upfront (~$20-100k) to a game developer willing to forfeit licensing rights. That’s nice: imagine being barely out of high school and receiving a 5 figure check. Things get tougher later on: if the game becomes a success with millions of downloads, the game developer will barely benefit from it, receiving a couple more checks for small amounts. And that’s it: all other revenues go to the publisher.

There are countless articles and subreddits claiming that publishers are ruthless and ripping off independant game creators. I find it a biased explanation to a basic business dynamic: as a publisher, you can distribute games better than anyone. Thus, you can either suffocate independant games by distributing yours or help indepent game creators share their craft with the world. By doing the latter, you have better games, and more profits.

An interesting question is whether or not independent game developers can compete. In my opinion, they could, but they would need to educate themselves business-wise. Being able to make a hit and being able to run an indie studio are completely different things. You need to have a statistical approach to game design, test the market, run ads, monetize, invest in winners, etc. It is a game for financiers. By the way, we at The Family are cooking up something directly related. Let me know if you’re interested ;)

Game theory

Just like economics, gaming can be looked at through the lens of cognitive sciences.

9/ Where are the casinos for gamers?

Celia Hodent was the former Lead UX Strategist at Epic Games (makers of Fortnite) and is the author of the riveting book The Gamer’s Brain. In her blog, she candidy explains parts of what made Fortnite such a success: they understood the gamer’s psychology and translated that into the right in-game stimuli. She also confirms that nothing was intentionally added to the game to create addiction [🇫🇷].

As someone who used to play a lot (3+ hrs per day) and managed it well with other aspects of my life, I can fully appreciate the distinction between pleasure and addiction. Yet there is no denying that gaming can resemble gambling by several aspects.

Ultimate Team is a mode available across several EA Sports games (including FIFA) that entices players to make large in-game purchases to build an ever better team. Your competitors only get better, so you have to spend more if you want to stay in the game. This mode now represents 28% of all EA Sports revenues! The more you play, the more you want to win, the more you pay. Typical gambling dynamics.

I am not pointing fingers. Addiction can happen to anyone, and I don’t believe a gaming addiction is better or worse than, say, a Netflix addiction or a gambling one. However, when a particular item can create addiction, it is paramount that governments regulate, but also that market operators participate in the self-regulation. For instance, Apple introduced features to reduce users’ screen time, which would never have been done directly by TikTok, Instagram or Snapchat. The market operator forced them into it. I believe the platform that will have the upper hand in cloud gaming will need to tackle the great challenge of regulating potential issues.

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s look at the business opportunity. If gaming is similar to gambling, where are the casinos for gamers?

Casinos are high fixed costs, capex-intensive businesses, no matter how profitable they are. With the platform design of the gaming industry it would be possible to create a scalable infrastructure to make substantial profits from gaming.

And sure, some online betting platforms are starting to allow bets on esports. This is good, but far from capturing the real potential of this opportunity. Cloud gaming could allow for the creation of a whole universe of virtual economics: investments, currencies, ads, bets, real estate, bets. A Metaverse, with its own economics, rooted with real-world money. And I think the simplest way to frame it is to see it like a casino: a magical place designed to thrill players and have them participate, generate content, spend money, invest.

This could be the perfect place to distribute new, real-life items: what better place to have a concert, broadcast a movie , stream your new single, advertise your business than the place where people are spending all their time & focus.

10/ The CFO stuff: gaming is a serious matter

There are many, many other things that could be said about the industry, especially from a financial angle: how it evolved from its early, passion-driven days and became a massive business; how M&A was instrumental in creating large editors (Activision-Blizzard, for instance) and franchises; how business models have evolved from simple sales to subscription and in-game upsell; how capital markets are responding super well to gaming (eToro’s simili-ETF for gaming was up 54% in 2019!).

I would just like to end (at last) this piece by saying that I am very long on gaming. I believe there are incredible opportunities for investments, businesses and jobs in that space - especially if you’re interested in finance.

So grab your controller and let’s play 🎮